The Holocaust: Still a Story Worth Telling?

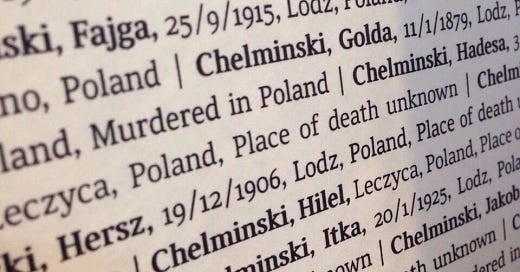

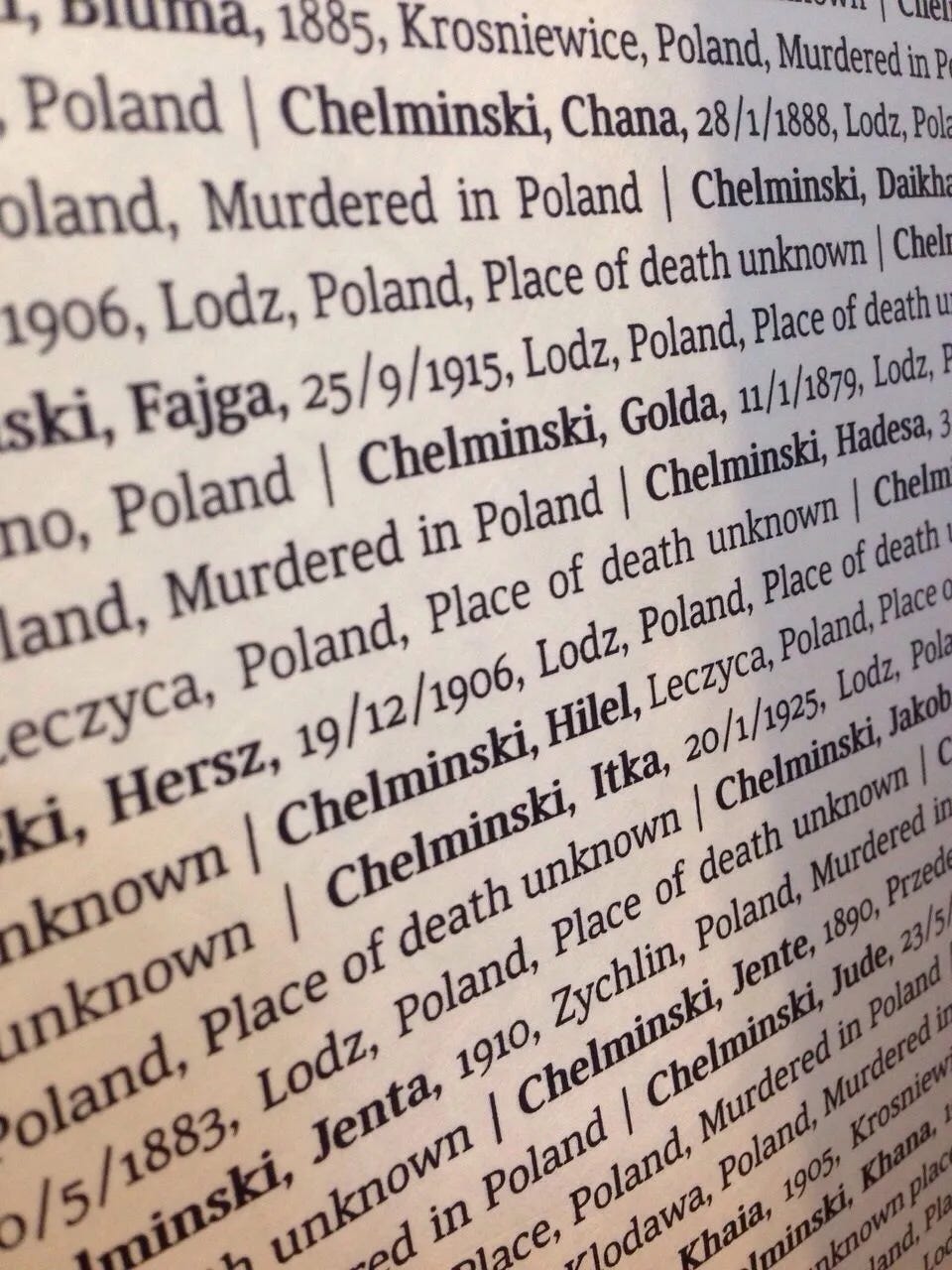

Ten years ago, my daughter took this photo at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw.

A wall, etched with the names of Polish Jews who perished in concentration camps.

Chelminsky. Chelminski. Chelminsky from Łódź. Chelminsky from Kłodawa—my family’s village. Chelminski from dozens of towns now lost to time, scattered across Poland.

Were they relatives? Just namesakes? It doesn’t matter. “Fun ünzere,” my grandfather would have said in Yiddish. “They’re ours.”

There’s no denying that for Jews—especially those of us born in the 20th century, children or grandchildren of Holocaust survivors—the legacy of Nazi extermination carries a weight that feels rawer, closer, more personal than it does for the rest of the world.

Many members of my grandparents’ families died in camps or were swallowed by the chaos of war. When I was growing up, the wounds of history didn’t just refuse to heal—they still bled.

And it’s true: this isn’t a sentiment universally shared. Even the most compassionate, humane, and deeply philo-Semitic non-Jews experience the Holocaust differently. No less tragic—just less intimate.

To some, it’s a horrific chapter in a history book.

To us, it’s a scar carved into our DNA.

As the years pass, the Holocaust begins to fade from the world’s collective consciousness. It’s reshaped by other narratives, co-opted, diluted.

And I’m not just speaking of deniers or revisionists—who, alarmingly, seem to be growing like weeds. I’m talking about the everyday person, for whom the sting of the Holocaust, its unimaginable cruelty, begins to feel like just another tragedy among many.

This year marks 80 years since the end of World War II and the liberation of Auschwitz. In today’s world of instant everything, that feels like an eternity. For many, it’s as remote as the Crusades or the conquest of the Americas. Exam material. No longer a living source of reflection or action.

We once believed the Holocaust was a universal tragedy whose lessons would stand eternal, unshakable.

We were wrong.

Because while it is humanity’s greatest tragedy, its lessons have not aged well. They sound repetitive. Their relevance is diminished or twisted to serve other causes—worthy, perhaps, but not equivalent.

With a few shining exceptions, we’ve failed to update the way we teach and remember the Holocaust—failed to keep its message resonant in today’s world.

The enormity of the Jewish Holocaust remains incomprehensible. But the way we speak about it—its moral call to action—must evolve.

Can non-Jews still connect with a tragedy that took place "in a faraway land, long ago"?

Can young Jews, who carry the memory in their blood but feel the distance of time, understand its central place in our story—and in their own?

And more importantly:

Can we still draw lessons from this tragedy that are relevant today, that guide us toward becoming a better society?

These aren’t rhetorical questions. And they’re certainly not small.

Yes, we must keep teaching the facts. The history hasn’t changed. But more urgently, we must emphasize how this story should lead to action. Its lessons must be reimagined and made relevant.

For decades, the standard takeaway has been:

“Those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it. Never again.”

But today, that sounds hollow.

How can “Never Again” be our rallying cry when, since 1945, we’ve witnessed countless tragedies—not identical in scale, but eerily similar in their systematic brutality?

How can we shout “Never Again” in a world drowning in hate speech, discrimination, and killings based on religion, gender, and identity?

The hard truth is: even with the knowledge of history, humans are still capable of repeating it.

Worse—we’re capable of refining its horrors.

The belief that simply knowing history will stop us from reenacting it is wishful thinking.

A dangerous simplification.

And the biggest mistake of all?

Failing to place the emphasis where it truly belongs: on action. On individual responsibility. On what each and every one of us must do to ensure “never” really means never.

(I hate to quote Arjona, but…)

The Holocaust will retain its relevance only if it becomes a verb—not a noun.

In a chaotic world, meaningful action starts with speaking out for what’s right—whether the injustice affects you directly or not.

Eighty years after Auschwitz, we must never forget the upstanders—the thousands who resisted, who sheltered, who saved, who fed, who defied the Nazi regime.

Not just the famous names—Oskar Schindler, Raoul Wallenberg, Irena Sendler—but the thousands of anonymous, everyday people who risked their lives to do what was humanely right.

They were far fewer than the bystanders who stayed silent. But they existed.

They saved lives.

They made a difference.

They showed us what courage looks like.

And that kind of courage still matters. In big ways and small. In actions that cost us something. In standing up when the crowd stays quiet.

Time dulls the sting of every tragedy.

But courage?

Courage never goes out of style.